Unlike previous shifts, this transition is not merely about replacing one fuel with another, but involves a complete overhaul of the energy system, bringing significant political, technical, environmental, and economic disruptions. At the heart of this transition lies hydrogen, a key player that has long been missing from the clean energy puzzle. The question now is whether hydrogen will exacerbate or alleviate these disruptions and in what ways it will shape the future of global energy.

Hydrogen´s role in this energy transition is poised to be transformative, with the potential to significantly disrupt existing energy value chains. The urgency to address climate change has propelled hydrogen into the spotlight, with many seeing it as a crucial component of the future energy mix.

According to IRENA’s 1.5 °C scenario, clean hydrogen could account for up to 12% of final energy consumption by 2050, with the majority produced using renewable sources and the remainder from natural gas combined with carbon capture and storage.

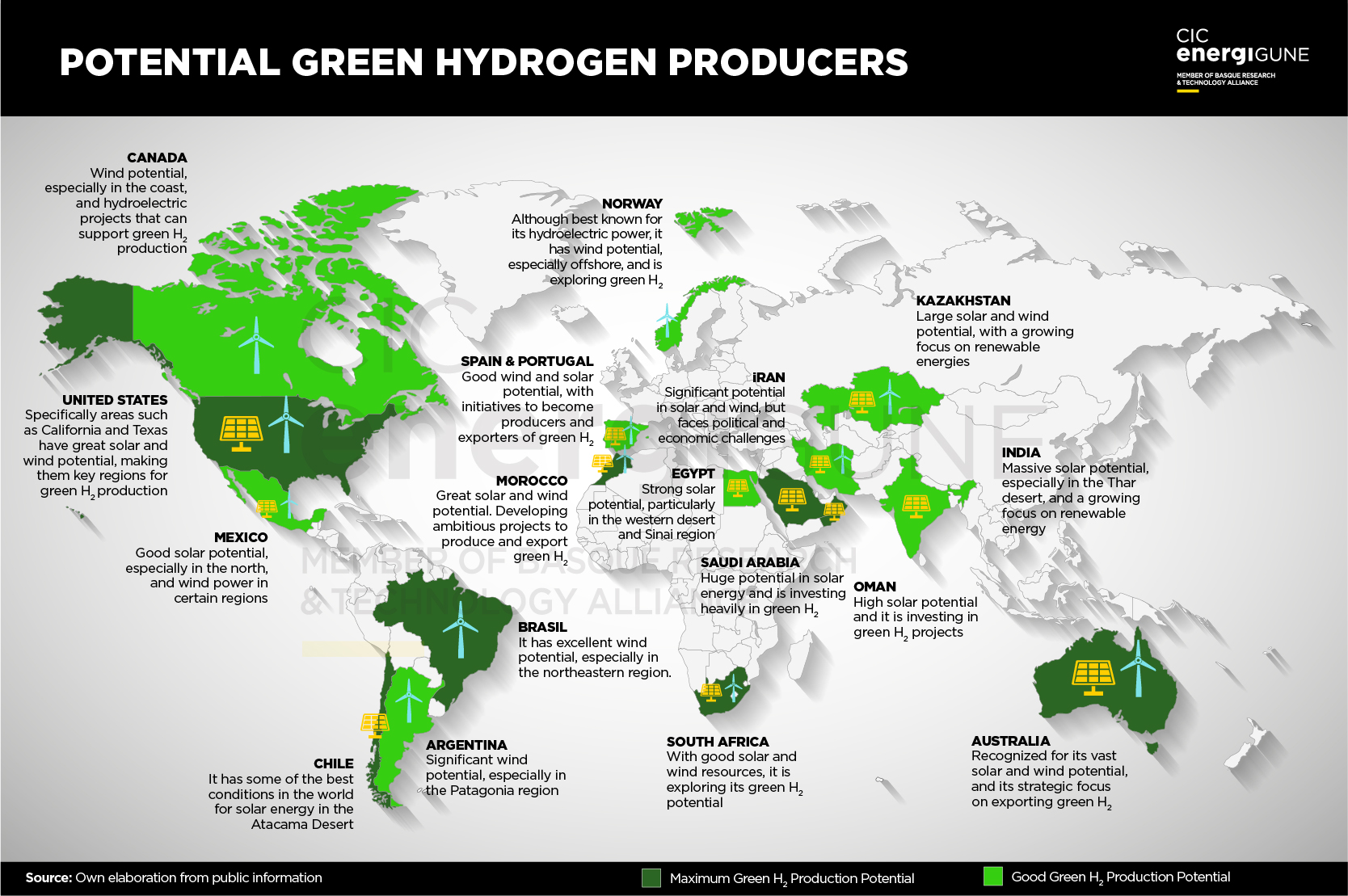

This shift towards hydrogen is expected to further regionalize energy relations, as the cost of renewable energy continues to fall while the expense of transporting hydrogen remains high. As a result, energy trade is likely to become more localized, with countries possessing abundant low-cost renewable energy emerging as key producers of green hydrogen. This will have significant geopolitical and geo-economic implications, potentially creating new power nodes in regions that can combine renewable resources with the capacity to export hydrogen to large demand centers.

Now, let´s explore the key geopolitical and geo-economic implications of this shift:

-

Competition and Market Dynamics in the Hydrogen Economy

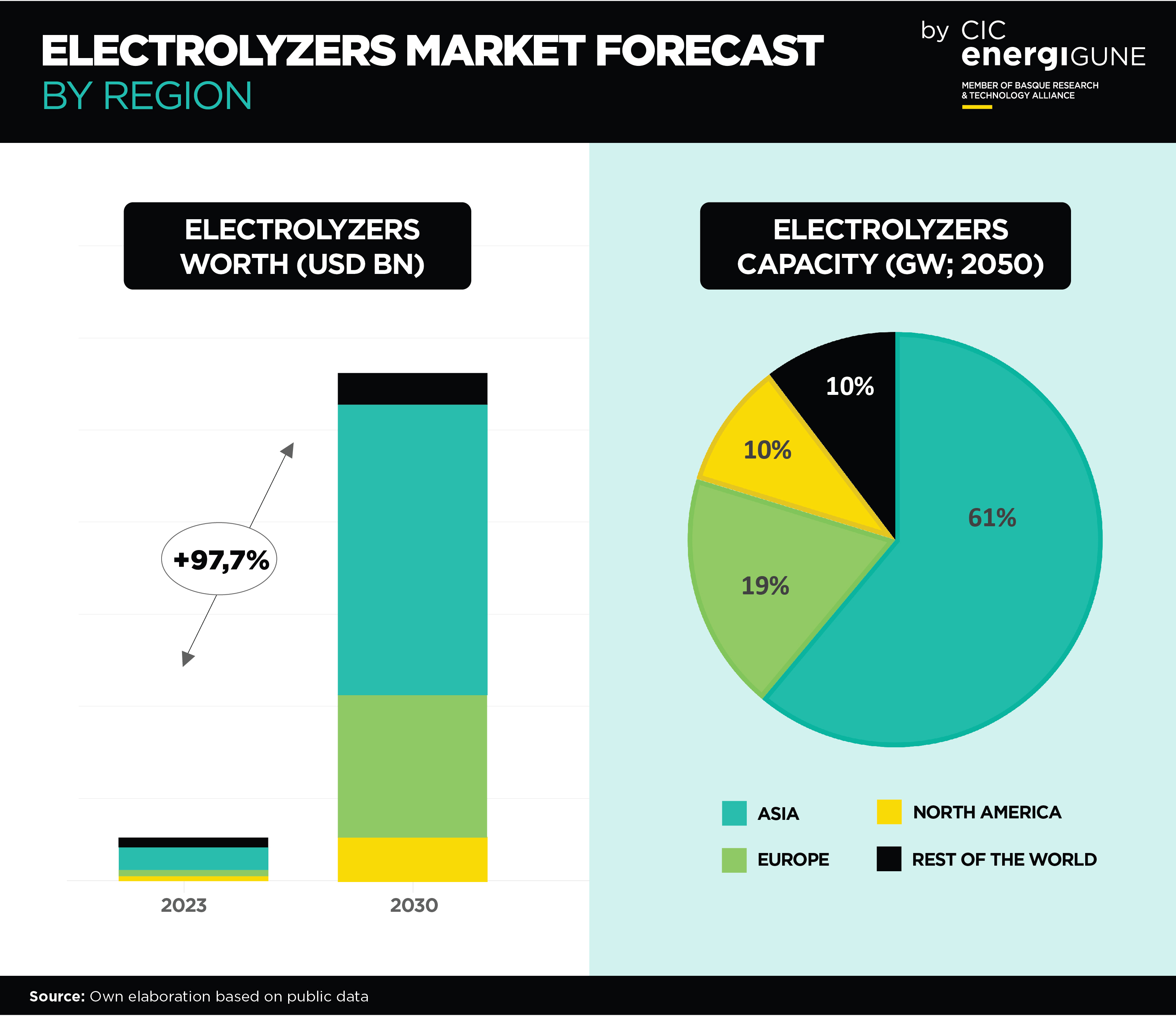

Unlike the oil and gas industries, the hydrogen business is expected to be highly competitive and less profitable. Hydrogen production is fundamentally different from fossil fuel extraction; it is a conversion process that can be performed in many locations, thereby limiting the potential for capturing the kind of economic rents that fossil fuels currently generate. As green hydrogen costs continue to decline, the market will likely see the entry of numerous new players, making it even more competitive. This heightened competition will likely prevent any single entity from dominating the market, which is a departure from the current dynamics of the oil and gas sectors.

-

Evolving Trade Relations and Diplomacy

The rise of hydrogen will also create new patterns of trade and diplomatic relations. Unlike the 20th-century energy relationships based on hydrocarbons, the emerging hydrogen trade is characterized by a growing number of bilateral deals. Over 30 countries and regions have developed hydrogen strategies that include import and export plans, signalling a significant increase in cross-border hydrogen trade.

Countries that have not traditionally engaged in energy trade are now forming bilateral relations focused on hydrogen-related technologies and molecules. This shift in economic ties could also lead to changes in political dynamics, as countries seek to secure their positions in the burgeoning hydrogen market.

Hydrogen diplomacy is becoming an increasingly important aspect of economic diplomacy, with countries like Germany and Japan leading the way. Many potential hydrogen importers are already actively engaged in dedicated hydrogen diplomacy, while exporters are similarly incorporating hydrogen, particularly green hydrogen, into their high-level diplomatic strategies.

-

Economic Diversification for Fossil Fuel Producers

For countries that currently rely on fossil fuel exports, clean hydrogen presents an attractive opportunity to diversify their economies. These nations can leverage their established energy infrastructure, skilled workforce, and existing trade relations to develop new export industries focused on hydrogen.

While blue hydrogen, which is derived from natural gas, seems a natural fit for these countries, many also have significant renewable energy potential that could enable them to transition directly to green hydrogen. Countries like the United Arab Emirates, Australia, Oman, and Saudi Arabia are exploring such dual approaches. However, it is important for fossil fuel producers to continue developing broad-based economic transition strategies, as hydrogen alone will not fully compensate for the expected loss in fossil fuel revenues.

-

Regional Production Potential and Investment Risks

The technical potential for producing green electricity, and consequently green hydrogen, far exceeds estimated global demand. However, the ability to produce large volumes of low-cost green hydrogen varies widely across different regions. Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Oceania have the highest technical potential, but realizing this potential depends on a range of factors, including existing infrastructure, the current energy mix, the cost of capital, and access to necessary technologies. Additionally, soft factors such as government support, the investment climate and political stability will play crucial roles in determining whether this potential can be realized.

Despite higher project finance costs in countries with higher risk profiles, investment in green hydrogen is still likely to flow into these regions, provided the revenue potential is sufficient. This dynamic mirrors the upstream oil and gas sectors, where investment often occurs despite significant country risks. However, there are limits to this trend, as countries experiencing turmoil may struggle to attract investment due to the immense risks involved in doing business in such environments.